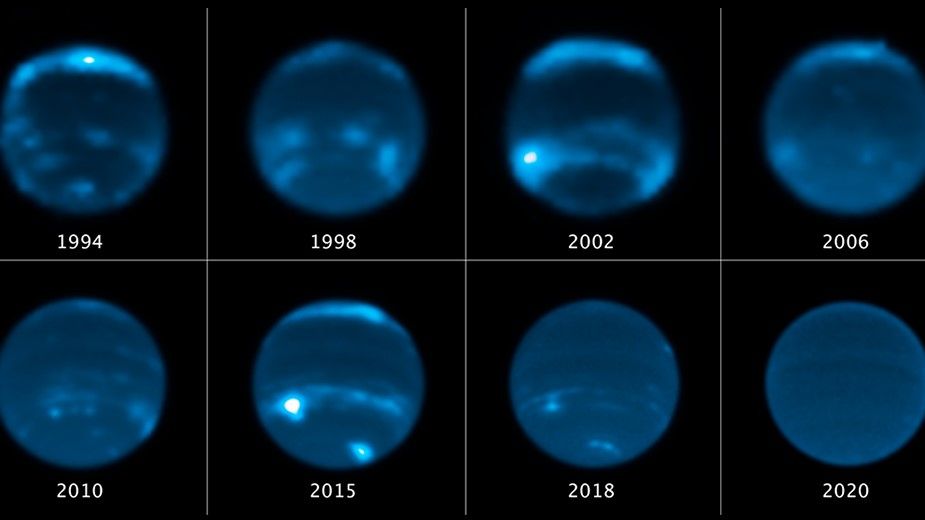

As the animations below dramatically illustrate, it really has been boom year for snow in the western United States. That’s especially so for water-starved California, as well as the megadrought-afflicted Colorado River Basin, whose dwindling waters support a $1.4 trillion economy.

Before-and-after satellite images, one captured on April 8, 2022 by the NOAA-20 satellite, and the other on April 10, 2023 by the Suomi-NPP spacecraft, show a dramatic difference in snowpack in the mountains of the American West. Currently, snowpack is well above average nearly everywhere. (Credit: Images from NASA Worldview, animation by Tom Yulsman)

The incredible snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range continues to make headlines — especially as a burgeoning heat wave threatens to cause dramatic melting, raising already high flooding risks. As of April 26, snowpack levels throughout the Sierra Nevada were more than 200 percent of average for the date. In the southern Sierra, the tally was greater than 300 percent of average.

Those kinds of numbers are not uncommon right now throughout the U.S. West, as this map shows:

Credit: USDA/NRCS National Water and Climate Center

All those blues and greens show where snowpack is above average.

The bounty of snow in the mountains of the Colorado River Basin is a relief for the 40 million people in seven states, Mexico, and numerous Indian tribes who depend on its waters. The two great reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, that have been essential to meeting their water needs, have declined to record low levels. And other reservoirs in the basin have seen their water levels dwindle dramatically.

A Reprieve

But now, the snowpack offers hope that further declines can be avoided — at least during the coming warm season. Based on the current forecasts, reservoir storage for the basin as a whole will be at about 44 percent of capacity on Sept. 30, the end of water year 2023. That’s up from 33 percent at the beginning of the water year on Oct. 1, 2022. A modicum of good news for a change — but almost definitely not in the long run.

Before-and-after satellite views of the Colorado Rockies, the first captured on April 4,2022 and the second on April 16 of this year. (Credit: Images from NASA Worldview, animation by Tom Yulsman)

“This winter’s snowpack is promising and provides us the opportunity to help replenish Lakes Mead and Powell in the near-term — but the reality is that drought conditions in the Colorado River Basin have been more than two decades in the making,” said U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton, in a statement.

Recent research shows that the region has been in the grips of the worst such drought in the region for at least 1,200 years. A little more than 40 percent of its severity was attributed in the study to human-caused climate change, largely from warming temperatures that have caused increasing aridity.

As Touton notes, “Despite this year’s welcomed snow, the Colorado River system remains at risk from the ongoing impacts of the climate crisis.”

Landsat-8 views of the headwaters region of the Colorado River show a dramatic difference in snowpack between April of 2022 and 2023. In both images, water bodies are artificially rendered in blue to make them stand out. (Credit: Images via Sentinel Hub, animation by Tom Yulsman)

Assuming this year’s bounty of snow produces the expected runoff into streams and rivers — which is not actually a given — it will buy policymakers a little more time to make some very hard decisions about how to cope with an inescapable fact: Much more water is being taken for farming, industry, and municipal use than has been flowing in the Colorado River. That is, of course, why lakes Mead and Powell have dwindled to record lows. And thanks to the climate crisis, in the long run, the deficit in flows is not likely to be reversed.

That long-term outlook is due to warming temperatures from the mounting concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere — which continued their historically high rates of growth during 2022, according to NOAA scientists.

“The bottom line is that in order to see any kind of decrease in the CO2 growth rate, decreases in emissions have to be sustained and significant,” says Arlyn Andrews, chief of NOAA’s Carbon Cycle Greenhouse Gases Group.

Right now, we’re nowhere near seeing decreases in emissions. Quite the opposite. In 2022, global energy-related CO2 emissions grew by 0.9 percent, according to the International Energy Agency, reaching a record high of nearly than 37 billion tons.