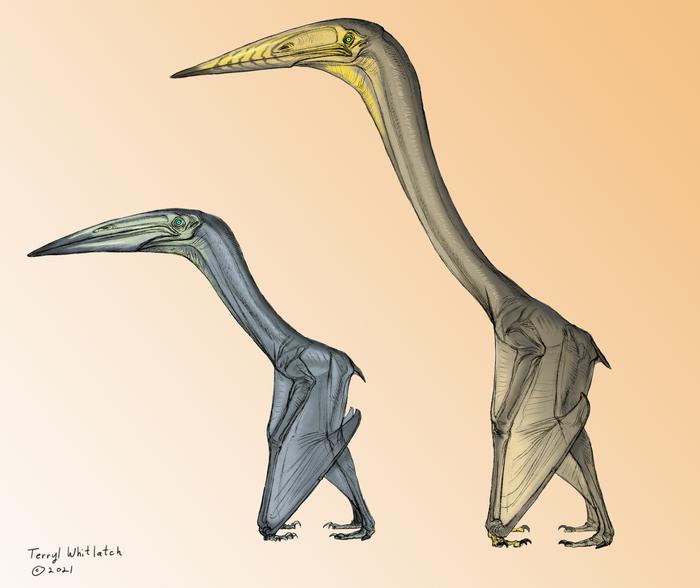

Paleontologists have long debated whether pterosaurs could fly. An analysis of fossils from two separate species of the ancient, winged dinosaur relatives suggest that not only did they fly, but also at least one species likely glided on air currents while another probably flapped its wings, according to a report in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Researchers determined these different abilities by using CT scans to analyze the fossilized bones. Scanning the humerus of Arambourgiania philadelphiae revealed a series of spiraling ridges inside the hollow bone of the creature with a 30-foot wingspan hollow. That internal bone structure resembles that of the modern vulture, which soars on thermal currents.

Probing the humerus of Inabtanin alarabia, which has a 15-foot wingspan, showed an entirely different structure inside the hollow bone. The scans exposed internal supports resembling the struts of an airplane’s wing, which are also found in the bones of contemporary flapping birds.

Analyzing Fossilized Pterosaur Bones

A confluence of fortune and technology made the findings possible. When Jeff Wilson Mantilla, curator at Michigan’s Museum of Paleontology, and Iyad Zalmout, from the Saudi Geological Survey, found the specimens in 2007 in Jordan, they were amazed at how well-preserved the fossils were, which date back to 66 million years to 72 million years ago. Pterosaur bones are delicate and are often found broken into pieces.

“The majority of pterosaur fossils we have are just completely flat like pancakes,” says Kierstin Rosenbach, who was a graduate student at the University of Michigan at the time of the study.

These two specimens were both found relatively intact. “It is pretty rare to find pterosaurs at all, but to find them preserved in three dimensions is even more rare,” Rosenbach says.

Rosenbach’s involvement represents a confluence of luck and tech. Mantilla, her graduate advisor, had brought the fossils to the university for examination. When Rosenbach joined his group in 2016, paleontologists were just beginning to adopt CT scanning. Rosenbach had used the technology as an undergrad — but on different species. It made perfect sense for her to scan the fossils.

Read More: 5 Of The Most Interesting Pterosaurs

Comparing Modern Bird Species and Pterosaurs

She was initially surprised by the spiral structures inside the A. philadelphiae humerus. Then she started comparing it to bones of many living bird species.

“The only other organism I’ve seen them in is in vultures,” says Rosenbach. “Vultures soar, rather than flap.”

How and why the two different pterosaur species evolved at a similar time and location to have such different bone structures remains a mystery and is up for speculation.

“It could be the environment, it could be foraging style, it could be competition with other similar animals, and it could be simply just a function of their body size and the shape of their wings,” says Rosenbach. “It’s most likely a combination of all of those things.”

Read More: Do We Still Have Any Species Today That Are Descendants of Dinosaurs?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.