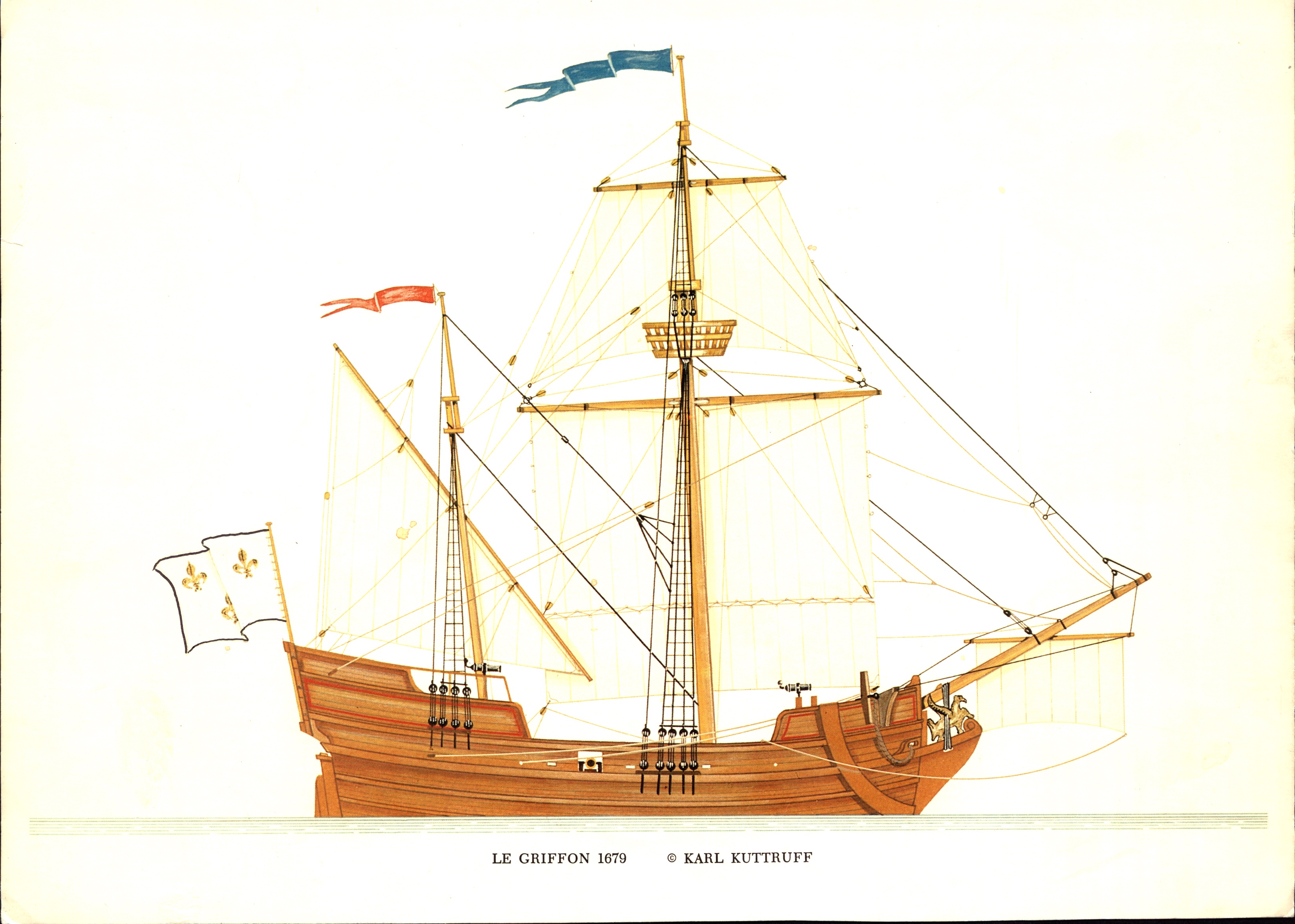

In September 1679, a French trader and explorer arrived near Green Bay, Wisconsin, with his new merchant ship, Le Griffon. The ship was loaded with furs and other commodities, and the captain was instructed to sail it back to a port in eastern Lake Erie.

The trader, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, headed south in a canoe with a team of explorers. It was the last he saw of Le Griffon. The ship sank in a storm and has not been seen since.

In the 345 years since the vessel sank, amateur relic hunters have announced many Le Griffon sightings, only to have state officials deem the artifacts as inauthentic. Underwater archeologists say Le Griffon has long been a target for hoaxes.

The Origins of Le Griffon

Le Griffon was one of the first European commercial vessels to sail the Great Lakes. Construction began in 1679, and it launched in August of that year.

La Salle, then in his mid-thirties, was the son of wealthy merchants. He grew up in a port city on the River Seine, about 50 miles from the English Channel. As a young adult, La Salle became a Jesuit priest but left after his repeated requests for an assignment in a faraway land were denied. He joined his brother in Canada, where he sensed that explorers enjoyed both wealth and prestige.

Trade, particularly among furs, was a means to an end for an explorer seeking funding. La Salle was interested in exploring the Mississippi River to see whether it flowed down to the Gulf of Mexico and could be used for transportation.

La Salle had Le Griffon built with the intention that it could navigate from the east of Lake Erie, near Buffalo, up Lake Huron, and into Lake Michigan, where there were fur trading posts.

The Disappearance of Le Griffon

Although there are legends that make it sound as though Le Griffon slipped into the fog and was never seen again, historians do have many primary sources documenting the vessel’s disappearance.

“We know quite a bit. LaSalle wrote a pretty detailed letter in 1681,” says Brendon Baillod, president of the Wisconsin Underwater Archeology Association.

In 1681, La Salle sent two explorers to search for the remains of the ship. They returned with substantial pieces as well as insight from the local Potawatomi people.

After La Salle left Le Griffon, he learned the ship sheltered at an island near the tip of Green Bay for the night. The next morning, the Potawatomi recognized a violent storm was imminent and warned the captain not to set sail.

“He replied that his ship was not afraid of the winds and he would do as he pleased,” Baillod says.

Are there any remains of Le Griffon?

After Le Griffon left the island shelter, it headed out into the storm and was lost at sea. La Salle’s letter indicated the explorers he sent in search of the wreck were able to recover recognizable pieces of the vessel. Given that it was the only European vessel on Lake Michigan at the time, Baillod says there would be no confusion as to the pieces’ origins.

Over time, scuba divers and wreck hunters have claimed to have found the sunken ship. However, Baillod says the wooden ship would not have survived 345 years underwater because of the unique area where it sank.

Read More: 4 Famous Shipwrecks That You Can Visit

Le Griffon sank to a part of Lake Michigan with a limestone substrate. The area is not particularly deep, about 80 feet. “The waves really move the water, even at 80 feet below,” Baillod says. “I would not expect any wooden remains from 1679 to remain.”

At best, Baillod says iron pieces might be scattered about. But, Le Griffon is thought to be somewhere in a 100 square-mile area, which would make searching extremely difficult.

Despite these realities, hosts of explorers have claimed to have found the legendary ship.

The Hoaxes of a Lost Ship

Starting in the 1930s, Baillod says hoaxers began suggesting that Le Griffon had never been found because it was in Lake Huron, not Lake Michigan. “They cherry-picked the records to support their claim,” he says.

For Le Griffon to have made it to Lake Huron, Baillod says it would have had to pass through the Straits of Mackinac, where fur traders would have seen the ship. There was a Jesuit mission at St. Ignace, and the vessel would have caught their attention, particularly because it was the first of its kind to sail those waters.

Why would anyone lie about finding Le Griffon? Baillod says that in recent years, the mention of finding the boat has landed amateur explorers in front of news cameras.

“It’s really been a target for pseudo-history and revisionist history. Anyone who finds a wooden wreck in the western Great Lakes tends to call it Le Griffon and call the media,” Baillod says.

A decade ago, scuba divers found a long pole they claimed belonged to Le Griffon. Michigan state authorities deemed it had been used for fishing sometime between 1880 and 1920. The scuba divers continue to insist they found Le Griffon, but scientists and state officials disagree.

“No one has found the Griffon. Until you hear a reputable archeologist with the State of Michigan say it has been found, you can rest assured it hasn’t been found,” Baillod says.

Read More: No One Knows How Many Shipwrecks Exist, So How Do We Find Them?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Emilie Lucchesi has written for some of the country’s largest newspapers, including The New York Times, Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri and an MA from DePaul University. She also holds a Ph.D. in communication from the University of Illinois-Chicago with an emphasis on media framing, message construction and stigma communication. Emilie has authored three nonfiction books. Her third, A Light in the Dark: Surviving More Than Ted Bundy, releases October 3, 2023, from Chicago Review Press and is co-authored with survivor Kathy Kleiner Rubin.