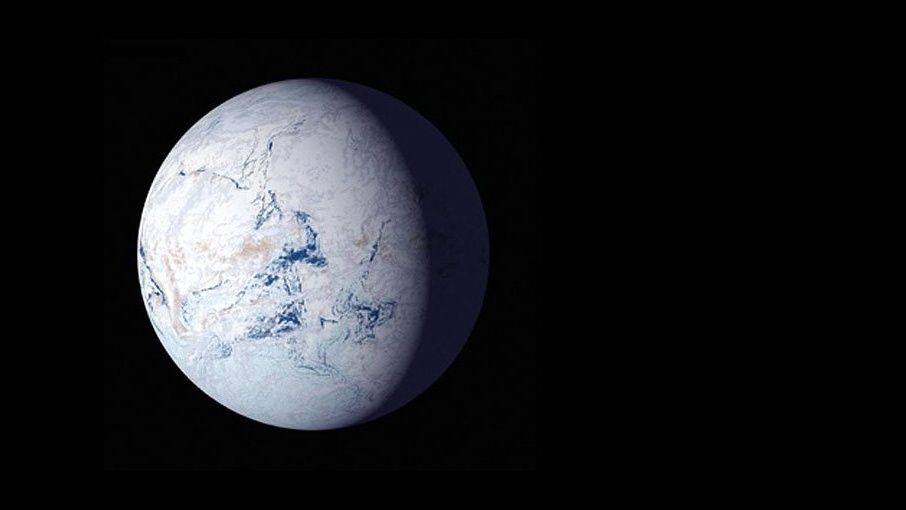

Anyone living on Earth between 720 million and 635 million years ago probably would’ve needed a jacket.

Geologists have long suspected that Earth’s temperature dropped dramatically during this time, resulting in a frigid “Snowball Earth.” But they’ve argued quite a bit about just how icy the planet got — specifically, whether thick glacial ice covered the entire globe, all the way down to the equator.

Now, new evidence found at the Tavakaiv, or “Tava,” sandstones in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado supports the notion that Snowball Earth was indeed a global phenomenon.

“This study presents the first physical evidence that Snowball Earth reached the heart of continents at the equator,” Liam Courtney-Davies, lead author of the new study and a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in a statement.

Related: Our luscious blue Earth used to be a frozen snowball

Why are the Tava sandstones an important piece of this puzzle? During the Snowball Earth period, Colorado wasn’t at its current northern latitude; rather, it sat at the equator as a landlocked part of the ancient supercontinent Laurentia. Currently, features of the Tava sandstones jut out from the ground at a few locations along Colorado’s Front Range, notably around Pikes Peak. For geologists, these features tell a fascinating story; they began as sands at the surface but were then shoved underground.

“These are classic geological features called injectites that often form below some ice sheets, including in modern-day Antarctica,” Courtney-Davies said.

If ice sheets were indeed responsible for pushing these rocks down into the subsurface, Courtney-Davies and his team wanted to find out exactly when this process was taking place.

The researchers took advantage of a dating technique called laser ablation mass spectrometry. Mineral samples were collected from the Tava rock, which are rich in iron oxide, and the team then hit them with a laser, releasing small quantities of the radioactive element uranium.

As uranium atoms decay at a known rate, the researchers were able to discern when the rocks were likely buried underground — sometime between 690 and 660 million years ago, which is smack-bang in the middle of Earth’s suspected Snowball phase.

Courtney-Davies also added that knowing more about this period in Earth’s history can help scientists understand the relationship between Earth’s climate and major evolutionary transitions in the history of life. For example, the first multicellular organisms, the ancestors of modern-day animals and plants, are thought to have emerged in the oceans not long after Snowball Earth eventually thawed.

“You have the climate evolving, and you have life evolving with it. All of these things happened during Snowball Earth upheaval,” Courtney-Davies said. “We have to better characterize this entire time period to understand how we and the planet evolved together.”

The study was published online Monday (Nov. 11) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.