Plastic littered across the world’s beaches can now be detected from space.

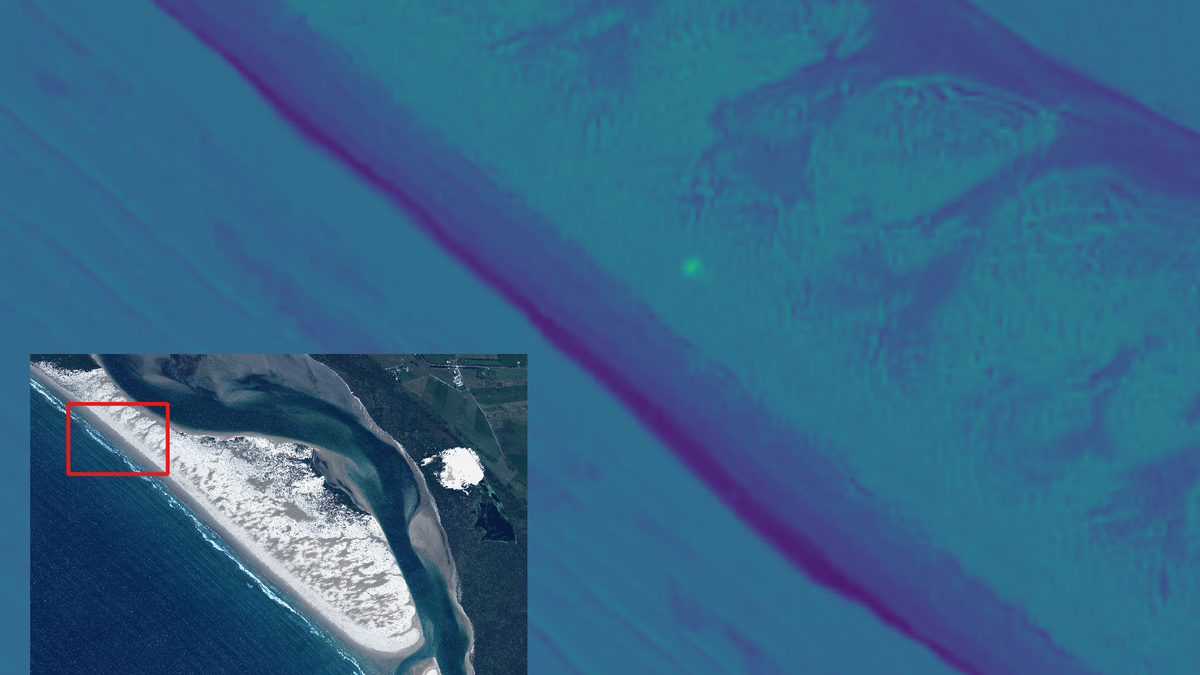

Researchers from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) in Australia developed a new satellite imaging technique that can spot plastics on beaches by measuring differences in reflected light from the debris compared to the surrounding sand, water or vegetation, according to a statement from the university.

This technique was successfully field-tested by satellites observing a remote stretch of coastline in Australia. By looking for unique spectral features in plastics, the satellites were able to accurately identify it on the beach from more than 373 miles (600 kilometers) above. In turn, this satellite technology not only improves the detection of plastic debris, but can also aid cleanup operations to support vulnerable environments, like beaches, the researchers said.

“While the impacts of these ocean plastics on the environment, fishing and tourism are well documented, methods for measuring the exact scale of the issue or targeting cleanup operations, sometimes most needed in remote locations, have been held back by technological limitations,” Jenna Guffogg, lead author of the study, said in the statement.

Related: 10 devastating signs of climate change satellites can see from space

This new research builds on existing satellite technology used to detect plastics floating in the ocean. The team developed a new spectral index, called the Beached Plastic Debris Index (BPDI), to identify patterns in reflected light collected by satellites as they pass over an area and specifically spot plastics that can easily blend in with sand.

The team placed 14 pieces of various plastic types on a beach in southern Gippsland, Victoria, to test the BPDI using WorldView-3, an Earth-observing satellite operated by Maxar Technologies. Data collected by the satellite showed that the new index was more successful at differentiating plastics on the beach compared to three other existing satellite technologies, which tended to mis-classify a shadow or water as plastic, according to the statement.

“This is incredibly exciting, as up to now we have not had a tool for detecting plastics in coastal environments from space,” Mariela Soto-Berelov, co-author of the study, said in the statement. “Detection is a key step needed for understanding where plastic debris is accumulating and planning cleanup operations, which aligns with several Sustainable Development Goals, such as Protecting Seas and Oceans.”

Next, the team aims to use the BPDI to scan coastlines more broadly and test its ability to detect plastic debris in real-world environments. This advanced satellite imagery technique is of growing importance as more than 10 million tons of plastic trash enter Earth’s oceans every year, and is estimated to increase to 60 million tons by 2030. This plastic can endanger wildlife when it is mistaken for food, entangles or traps animals, or further degrades into micro or nano plastics, the researchers said.

“We’re looking to partner with organizations on the next step of this research,” Soto-Berelov said in the statement. “This is a chance to help us protect delicate beaches from plastic waste.”

Their study was published Oct. 22 in the Marine Pollution Journal.