NASA’s newest space telescope has left scientists seeing distant stars — and galaxies.

The James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST), which launched in December 2021, has executed just five months of science observations. Astronomers knew the $10 billion telescope would offer a new view on the universe, but early observations have still blown those expectations away. In particular, JWST has carried scientists out deeper into the universe, farther from Earth and earlier in cosmic history than researchers had anticipated

“We’re really on track to realizing the dream of understanding galaxies at the earliest times,” Garth Illingworth, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, said during a NASA news conference held Thursday (Nov. 17) dedicated to early science results from the new observatory. “The last few months have been exciting, but a huge amount remains in front of us to learn and to gain insights into what is really happening in the first billion years of galaxies.”

Related: Dazzling James Webb Space Telescope image prompts science scramble

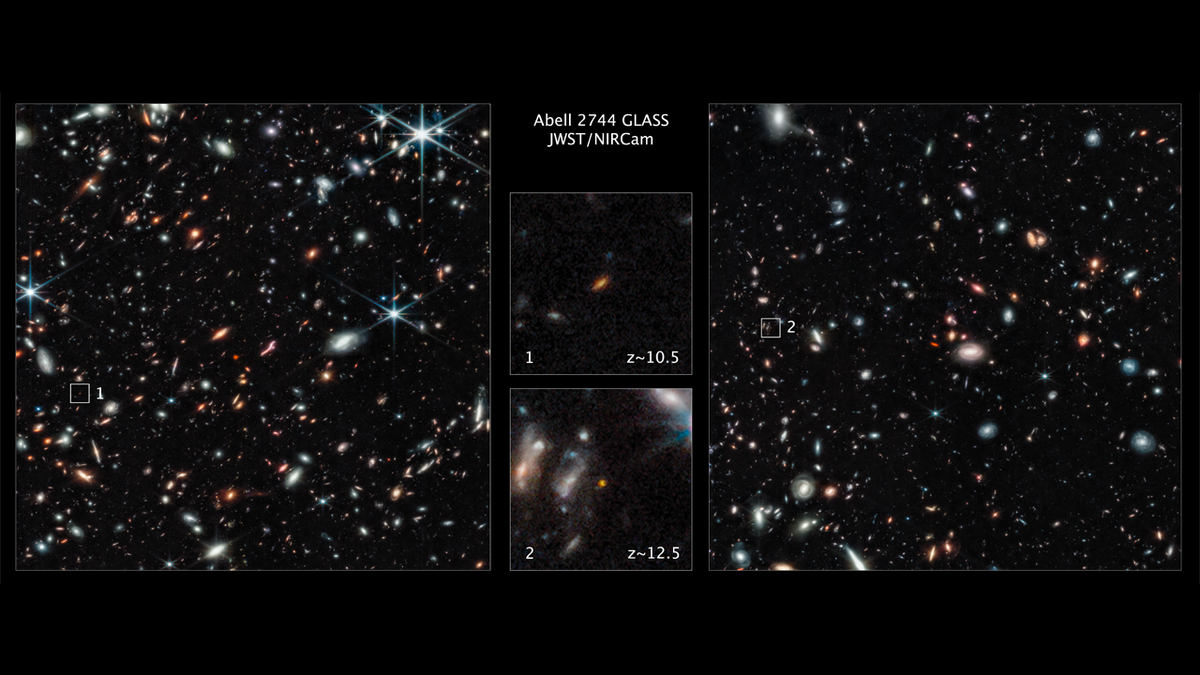

The very first science-quality image released by the JWST team — an image showing countless galaxies sprinkled across space — sparked a scramble as scientists hunted for the most distant galaxies in the observable universe, a quest that continued as the telescope settled into operations.

“One thing that really struck me in the early days of JWST images is how quickly our understanding of galaxies is changing,” Jeyhan Kartaltepe, an astrophysicist at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, said during the briefing. She looked back to the moment the first image was revealed, saying, “We were witnessing a once-in-a-generation moment where, just overnight, our capabilities and understanding of the universe were about to change.”

Because light travels at a fixed speed, observing distant objects means seeing them as they were in the past, so the most distant galaxies astronomers can see are also the most primitive.

Now, some of those early finds have been published in peer-reviewed studies. Perhaps the star of the show is a galaxy dubbed GLASS-z12, which two separate teams of researchers have used early JWST observations to date to just 350 million years after the Big Bang. The find made headlines in July but even now isn’t quite settled.

Since the detection, a ground-based facility, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, has offered “a tentative confirmation” of the distance analysis, Tommaso Treu, an astronomer at the University of California at Los Angeles and co-author on one of the new papers, said during the briefing.

However, sealing the deal requires new and different JWST data. The research to date identifying GLASS-z12 and other distant candidates has analyzed images. Scientists can estimate distances from images, but nearer galaxies have been known to masquerade as distant ones in this type of data.

A more reliable technique relies on what scientists call spectra, the barcode-like smear of light from an object separated by wavelength. It’s a type of data JWST specializes in, but the astronomers must wait as the observatory conducts the plentiful science already booked for its first year in space.

The researchers have asked that the observatory use a separate instrument to revisit the galaxy in the coming months. That hope comes through a program that allows the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland, which operates the observatory for NASA, to jump on fleeting opportunities that couldn’t have been predicted when scientists applied for time in the telescope’s first year. The astronomers have not yet heard back, Treu said; if the request is rejected, they will propose the work for the observatory’s second year, which begins next July.

But even without spectral observations in hand, Treu said he and his colleagues feel confident in their dating of GLASS-z12. “I think this is as solid as it gets at this point without JWST confirmation,” he said.

Early bounty

The finding, and the other identifications of super-distant galaxies scientists have proposed in the months since JWST started work, aren’t just curiosities. Identifying these primitive galaxies allows scientists to hone the timeline between the Big Bang and the universe as we see it today.

Astronomers had estimated how many galaxies they might find at these distances, but in JWST’s observations to date, candidates are proving more plentiful than expected. The bounty means that galaxies — and, in turn, the stars they’re made of — must have started forming earlier than scientists previously thought.

“Finding these really bright galaxies has opened up the whole ballgame,” Illingworth, a co-author on the second paper, said. Perhaps the first stars might have formed just 200 million years after the Big Bang, he said.

“That’s a happy surprise, that there’s lots of these kinds of galaxies to study,” Jane Rigby, Webb operations project scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said during the briefing.

“These galaxies we’re talking about are bright, and so they were hiding, just under the limits of what Hubble could do,” she added. “They were right there waiting for us — we just had to go a little redder and go deeper than what Hubble could do.”

The research is described in two papers published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters — one on Oct. 18 and one on Thursday (Nov. 17).

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.