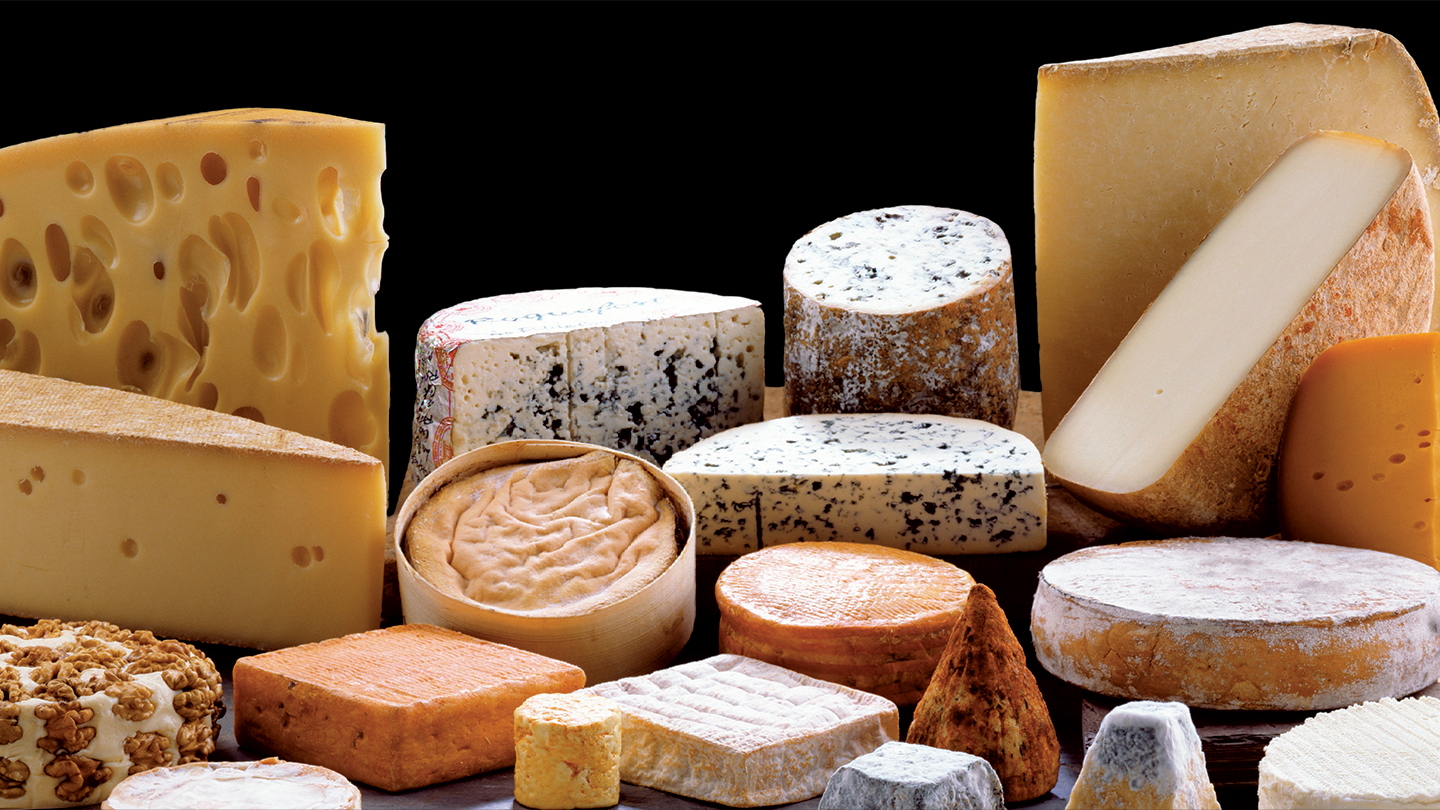

Cheese making has been around for thousands of years, and there are now more than 1,000 varieties of cheese worldwide. But what exactly makes some cheeses like Parmesan taste fruity and others, such as Brie and Camembert, taste musty has remained a bit of a mystery. Now, scientists have pinned down the specific types of bacteria that produce these flavor compounds.

The findings, described November 10 in Microbiology Spectrum, could help cheese makers more precisely tweak cheese flavor profiles to better match consumer preferences, say food microbiologist Morio Ishikawa and colleagues.

Science News headlines, in your inbox

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your email inbox every Thursday.

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

A cheese’s flavor depends on more than the type of milk and starter bacteria used to make the fermented dairy delight. A constellation of organisms that move in during the cheese-ripening process also contributes to the flavor (SN: 5/14/16).

Ishikawa, of the Tokyo University of Agriculture, likens these nonstarter bacteria to an orchestra. “We can perceive the tones played by the orchestra of cheese as a harmony, but we do not know what instruments each of them is responsible for.”

Previous research by Ishikawa and colleagues used genetic analysis, gas chromatography and mass spectrometry to link specific flavor molecules with specific types of bacteria on surface mold–ripened cheeses made from pasteurized and raw cow milk in Japan and France.

In the new study, to show that each bacterial suspect was responsible for producing the flavor compound it had been linked to, the team unleashed each type of microbe onto its own unripe cheese sample. The researchers then observed how flavor compounds in the cheese changed over 21 days.

Notably, Pseudoalteromonas — a genus of marine bacteria found in various cheeses — produced the greatest number of flavor compounds. And the microbes produced esters, ketones and sulfur compounds, known to impart fruity, moldy and oniony flavors in cheese.

Besides helping perfect popular cheeses, Ishikawa says, the findings might help cheese makers conduct new orchestras that would play new harmonies.