Modern birds evolved from dinosaurs, but it’s not clear how well birds’ ancient dino ancestors could fly (SN: 10/28/16). Now, a look at the fossilized feet of one nonavian dinosaur suggests that it may have hunted on the wing, like some hawks today.

The crow-sized Microraptor had toe pads very similar to those of modern raptors that can hunt in the air, researchers report December 20 in Nature Communications. That means the feathered, four-winged dinosaur probably used its feet to catch flying prey too, paleobiologist Michael Pittman of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and colleagues say (SN: 7/16/20).

Science News headlines, in your inbox

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your email inbox every Thursday.

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Other researchers caution that toe pads alone aren’t enough to declare Microraptor an aerial hunter. But if the claim holds up, such a hunting style would reinforce a debated hypothesis that powered flight evolved multiple times among dinosaurs, a feat once attributed solely to birds.

Toe pads are bundles of scale-covered flesh on the undersides of dinosaur feet, similar to “toe beans” on dogs and cats. Because the pads are points where the living animal interacted with surfaces, toe pads give paleontologists a “sense of where the rubber meets the road,” says Alexander Dececchi, a paleontologist at Mount Marty University in Yankton, S.D., who was not involved in the new study.

These contact points can paint a clearer picture of an animal’s behavior by providing “details that the skeleton itself wouldn’t show,” says Thomas Holtz Jr., a dinosaur paleobiologist at the University of Maryland in College Park, who was also not involved in the study.

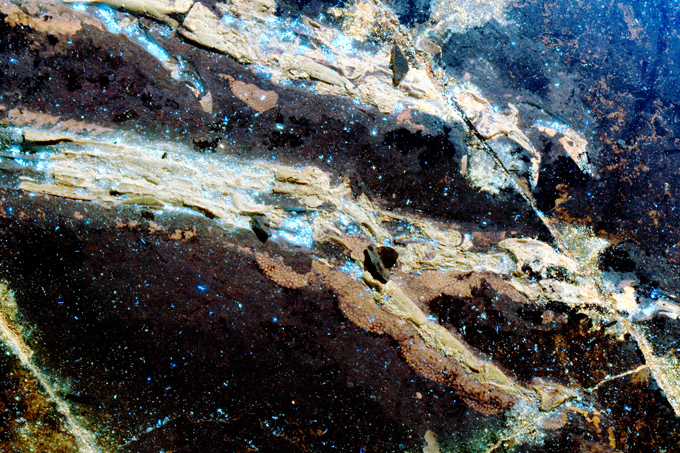

To investigate dinosaur toe pads, Pittman and colleagues turned to the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in Linyi, China. It “has arguably the largest collection of feathered dinosaurs in the world, and, importantly, they haven’t been prepared extensively,” Pittman says. Many of these dinosaur skeletons are still surrounded by rock, which is where soft tissues can be preserved. Such a specimen “gives us the best chance of finding this wonderful soft tissue information,” he says.

Using special lasers that cause the otherwise nearly invisible soft tissue in the fossils to fluoresce, the team found 12 specimens with exceptionally well-preserved toe pads among the thousands examined (SN: 3/20/17).

The team compared the fossil toe pads with those of 36 types of modern birds, whose toe pads vary with their lifestyle. Predatory birds, for example, have protruding toe pads with spiky scales for grasping prey, while ground birds that spend their time walking and running have flatter toe pads. The analysis showed that Microraptor’s toe pads and other aspects of the feet, like the shape of the toe joints and claws, are most like those of modern hawks. That similarity suggests that the dinosaur could hunt prey midair and on the ground like hawks do, the team says.

Other dinosaurs, like the feathered Anchiornis, had flatter toe pads and straighter claws, suggesting a terrestrial lifestyle. That’s in line with ideas about this dinosaur being a poor flier, Pittman says.

The idea that Microraptor hunted like a hawk is consistent with other fossil evidence. One Microraptor fossil has been found with a bird in its stomach, and Microraptor‘s skeletal and soft tissue anatomy suggest some powered flight capability.

There’s still more work to do to figure out how well the dinosaur may have flown. “Microraptor is not a bird, but a close relative. Just because it has feet like a predatory bird doesn’t necessarily mean it must be catching prey in the exact same way,” Pittman says. But Microraptor’s hawklike lifestyle “is a strong possibility,” he adds.

Subscribe to Science News

Get great science journalism, from the most trusted source, delivered to your doorstep.

Flight could have been useful to Microraptor when hunting, even if it couldn’t stack up to today’s fliers. Dececchi speculates that Microraptor’s anatomy probably prevented it from outflying birds, but may have helped it surprise otherwise out-of-reach prey, including flying and gliding animals.

“You only have to be fast or aerobatic enough to catch other things in your environment,” Holtz says. “So, it’s not improbable that [Microraptor was] catching things in the air on occasion.”

Other paleontologists are more skeptical that Microraptor hunted on the wing. “It would be a bit of a stretch to me to suggest that Microraptor was pursuing prey in an aerial context,” says Albert Chen, a paleobiologist at the University of Cambridge. The new findings inform only “what the foot was used for.”

Alternative hypotheses, such as a completely or partially terrestrial hunting style, could fit the data too, Holtz says, but the “feet are definitely playing a major role in their prey capture,” whether on the ground or in the air.

For now, the picture of Microraptor’s ecology remains fuzzy, but as lasers continue to increase the picture’s resolution, our understanding of dinosaur flight may reach new heights.