A mat composed of microbes may have preserved a series of 255-million-year-old indentations made in a sandy South African tidal bottom by a hulking amphibian, a new study says.

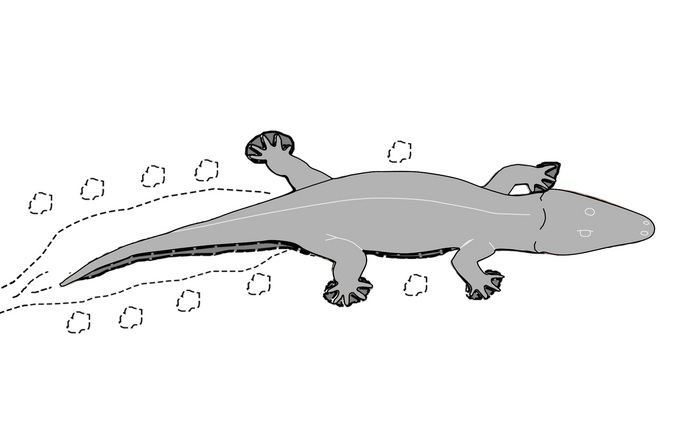

The remarkable shapes reveal that the nearly 2-meter-long rhinesuchid temnospondyl lurked for its prey and swam after it in the fashion of a crocodile. Like a prehistoric choreographer’s diagram, the impressions are a unique window into life on ancient earth shortly before the Permian Mass Extinction Event destroyed 90 percent of species on the planet.

Read More: The Late Permian Mass Extinction Explained

“The findings of the study are significant because they help to fill in gaps in our knowledge of these ancient animals,” the authors say in a statement. “The remarkable tracks and traces […] provide direct evidence of how these animals moved and interacted with their environment.”

Shallow Site

The Dave Green paleosurface, named for its late discoverer and landowner, covers about 600 square meters in the Karoo Basin, a large sedimentary basin that spans about two-thirds of South Africa. About 10 centimeters of sandstone now covers the paleosurface, which sits furrowed with ancient ripple marks. This land was once part of a tidal flat or lagoon that contained either fresh or brackish water, according to the research team from South Africa and Europe.

While researchers have studied the Dave Green site before, this team brought drones to take photographs from 10 meters high, and handheld 3D scanners, to render the rare indentations. Researchers have tried in the past to make plaster casts of the long, shallow forms and failed.

The resulting images captured a prehistoric crossroads frequented by both fish and tetrapods, four-legged creatures like the rhinesuchid temnospondyl. In addition to the latter’s markings, the team found three different pathways marked by small footprints that probably belonged to smaller tetrapods that had waded through the water.

Top Predator

The rhinesuchid creature coiled around the whole scene, making near-right-turns as it skimmed along the bottom. At times, it idled down there and looked up using eyes embedded in the top of its triangular skull. Then when it swam across the bottom, it did so with a writhing, sinusoidal movement that left a narrow path in the sand.

Crocodiles swim in a similar fashion, though they wouldn’t evolve for about another 50 million years, during the Late Triassic. But like them, the rhinesuchid probably tucked its legs under its body when it swam, given the relative lack of footprints.

Read More: Why Dinosaurs Survived the Late Triassic Mass Extinction

Soft mats of bacteria and single-celled organisms could have protected many of the indentations from erosion, the study says, especially those that lack ripple marks. Some of the oldest living structures on earth, microbial mats have embraced countless habitats, writes biologist Gisela Gerdes in a book chapter, including river bottoms.

The South African researchers acknowledge Dave’s role in first bringing the site to light in 1991, by contacting a professor at the University of Natal in South Africa.

The statement says that the study “demonstrates how important paleontological discoveries are often made by curious people bringing their findings to the attention of paleontologists.”