Tracy Criswell didn’t always want to be a scientist. Her initial interest was in music, specifically the flute. After she graduated from Xavier University with her Bachelor of Arts in Music, however, she realized that she didn’t want to spend the rest of her life teaching music. So, she went back to school for a biology degree, intending to pursue veterinary medicine. During her second year, however, she had the opportunity to work in a laboratory, which finally struck a chord . “As soon as I got involved in laboratory work, I was like, ‘This is it. This is where I belong,’” she said.

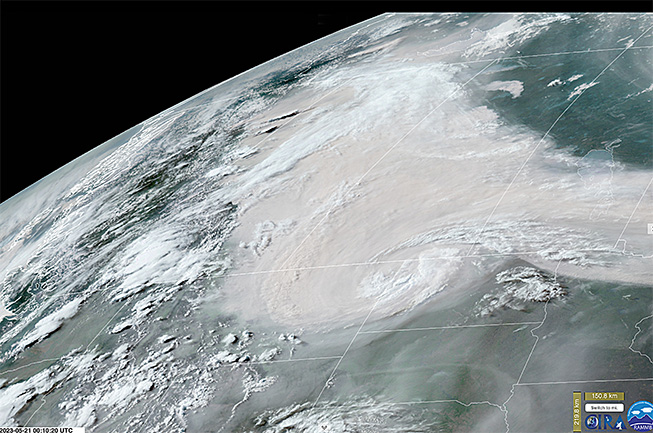

Today, Criswell is a cell biologist at Wake Forest University, where she studies processes that regulate skeletal muscle regeneration. With age, skeletal muscle’s ability to regenerate decreases, causing muscle mass and function to decline.1 In older women, changes in hormone signaling may play a role in impaired muscle regeneration.2,3 Criswell hopes that her research on the influence of age and sex on muscle regeneration will inform new therapies to help older adults maintain mobility, strength, and independence.

Tracy Criswell studies how muscle regeneration is affected by age and sex.

Wake Forest Institute For Regenerative Medicine.

How did you begin studying skeletal muscle regeneration?

It wasn’t intentional, but I feel like I always end up where I’m supposed to be. In graduate school, I studied cancer biology and the effects of radiation on cancer. During my postdoctoral fellowship, I studied cell signaling pathways involved in cancer. By this point, I had three young kids, and I decided I wanted to live near my parents. So, I sent my CV to several institutions in North Carolina, and someone from the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) contacted me. They needed a researcher to work on a skeletal muscle project.

The truth is, I didn’t know anything about skeletal muscle when I started. Fortunately, the faculty members at WFIRM with expertise in skeletal muscle biology and physiology took me under their wings. I realized that skeletal muscle is actually fascinating. It’s involved not only in movement, but in the maintenance of body temperature and glucose metabolism.

What led you to study muscle regeneration in the context of aging?

Once again, the aging aspect of my research came about by happenstance. I started out working on models of compartment syndrome, which occurs when someone injures a muscle and the tissue tries to swell. However, muscle is bound by membranes — almost like shrink wrap — so the swelling can’t go anywhere, and the blood vessels end up getting cut off.

For now, a fasciotomy procedure in which a doctor cuts between the muscle bundles to relieve the pressure is the only treatment for compartment syndrome. Fasciotomy has its own consequences since the muscle is being cut open, but it preserves the limb. We wanted to develop a small animal model of compartment syndrome to test other therapies.

We found that when we induced the compartment syndrome injury in young rats, they healed really fast, and there was no window of time to test therapeutics. That led us to study older rats. Older rats, like older people, heal more slowly.

Our bodies have all built muscles before; we all come from a single cell.

– Tracy Criswell, Wake Forest University

Why is that?

Skeletal muscle has its own population of stem cells, known as satellite cells, that become activated after injury. They differentiate into muscle cells to replace the damaged muscle, but they also replenish themselves. That’s important so that the stem cell pool doesn’t run out. When we get older, however, we don’t replenish the stem cell pool as well.

The stem cells are an important aspect of regeneration, but they’re not the only thing that matters. If we put young stem cells into young animals, the animals heal just fine. If we put stem cells from young animals into older animals, they don’t work as well. The environment plays an important role in whether the therapy will be effective. I can put healthy, growing stem cells into a muscle, but if that muscle is poorly vascularized, or fatty, or otherwise unhealthy, it’s not going to work as well as if I put those stem cells into a healthy, young muscle.

What that means for regenerative medicine is that we have to consider the patient as a whole. For stem cell therapy, we want to use the best cells we can find, but the tissue environment where we put those cells also has to be primed to accept them. We can’t expect cells to grow well in an inhospitable area, such as in inflamed or fibrotic tissue.

What kinds of therapies could improve muscle regeneration during aging?

We’re still pretty far away from using stem cell therapy to heal skeletal muscle. There are several problems with this type of therapy that haven’t been solved yet. First, we need a large quantity of cells. Autologous cell transplantation — taking the patient’s own cells and putting them back into the same patient — is the ideal scenario because the body doesn’t reject those cells. However, the patient’s stem cells might not be healthy enough, or the patient may not have enough of these stem cells.

The other option is to transplant stem cells from one person to another. In this case, the patient must be on immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of his or her life to prevent rejection. We have an immune system for a reason, though, and these drugs can increase the risk of infections and certain cancers.

To avoid these problems, I think that a better approach is to figure out how to get the body to fix itself. Our bodies have all built muscles before; we all come from a single cell. We have the programming to make all of our tissues, but it’s turned off most of the time. Understanding how those processes work could help us learn how to selectively turn on the developmental process again. For example, if a patient has a gap in a muscle but has at least some satellite cells, we could potentially fill the gap with a gel that contains growth factors to attract the muscle stem cells to fill the gap. We could also add other growth factors to the gel to bring in blood vessels and nerves.

What are you interested in studying next?

I’ve gotten more and more interested in studying aging in women as I’ve gotten older. It’s personal now! The estrogen that regulates our reproductive cycles also maintains several other systems in our bodies, including our skeletal muscles. During menopause when the ovaries stop producing estrogen, women become more susceptible to sarcopenia, or skeletal muscle loss due to age.

While hormone replacement therapy can increase estrogen levels, the problem is that it doesn’t mimic the natural cyclical regulation of hormones that occurs before menopause. I’m interested in exploring if we could engineer endocrine tissue to restore the body’s natural cycle of hormone regulation, which could help preserve muscle mass and function as women age.

I don’t want to live to be 150 years old; that’s not why I’m interested in aging research. However, as I get older, I do want to be able to walk down the street and get dressed by myself. Quality of life is what really matters as we age.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

References

- Yamakawa H, et al. Stem cell aging in skeletal muscle regeneration and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1830.2.

- Buckinx F, Aubertin-Leheudre M. Sarcopenia in menopausal women: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:805-819.

- Collins BC, et al. Estrogen regulates the satellite cell compartment in females. Cell Rep. 2019;28(2):368-381.e6.

This story was originally published on Drug Discovery News, the leading news magazine for scientists in pharma and biotech.